Everyone has got an opinion about Nigella Lawson. Ever since those photos first emerged last June of her then husband Charles Saatchi appearing to grasp her by the throat, every dinner party, coffee morning, school-gate gossip and working breakfast has thrilled over the details of her marital breakdown, divorce and the subsequent trial that saw her take the stand as a prosecution witness in the case against her and Saatchi’s long-time assistants, Francesca and Elisabetta Grillo.

One day she has been cast as a victim, the innocent party in an abusive marriage. The next, she’s a drug addict, castigated by the same media who once labelled her a saint. Her appearance at Isleworth Crown Court last December – where she admitted to taking cocaine “a handful of times” in the past and described her ex- husband as capable of “intimate terrorism” – drew such crowds and such obsessive media, one often forgot just who was on trial. “I did not have a drug problem. I had a life problem,” she told the judge. Yet everyone has always had an opinion about Nigella – whether it be about her being the former chancellor’s daughter, or her beauty, or her first marriage to the journalist and broadcaster John Diamond, or her second, hasty union with the advertising guru Charles Saatchi. Or about whether she should wear a burkini, or lick her fingers so lasciviously, or use so much butter. Everyone has an opinion. And everyone wants to share it.

I should know. Nigella Lawson is one of my oldest friends. This year, I spent Christmas Day with her, her family, and some friends. Well, wouldn’t you? It was no ordinary Christmas. It came just days after the case had found the Grillos not guilty of defrauding herself and Saatchi of £685,000, and at the end of a gruelling year. We found Nigella in her new kitchen in an airy, rented home in west London – a nice house, not big but welcoming, with an open-plan kitchen/ sitting room. She looked subdued and slim in black jeans and a black shirt, although she swore she’d gained weight. “I have been eating a lot of chocolate,” she said. Subdued she may have been, but she was far from beaten. Despite the emotional turbulence of the previous weeks, we found her doing what she does best: feeding the people she loves. She joked that her biggest headache in the preceding 24 hours had been finding a pot big enough in which to soak her turkey in brine overnight. At a time when thousands of homes in Britain were following her instructions to the letter, even she didn’t have the utensils she needed. We helped ourselves from a table groaning with food, and ate off paper plates till we could eat no more.

I first met Nigella when I was about 19 and she 21. She was a student at Oxford University and we had boyfriends who had been at school together – a pair of rather fey Etonians whom we had turned up to watch play in an old boys’ football match. I remember her being an amazingly beautiful, unusually friendly girl with great hair, who suggested we sit the match out in her car. We have never again watched football together but we became fast friends. At the time, she was living with her mother, Vanessa, and Vanessa’s husband, the philosopher Freddie Ayer, but I have no memory of meeting them. Freddie was teaching at Dartmouth College, in America, and the house felt strangely unlived-in. Already, Nigella seemed terribly grown-up and sophisticated. She was obviously clever, but never in a way that made me feel less so; she was cosy and nurturing. I remember her always having people round for supper – something other friends my age didn’t really do. She has cooked since childhood, “perched”, as she remembers it, “on a rickety stool and stirring while my mother gave orders”, and she often refers to her mother’s cooking in her books, despite their having a very difficult relationship. When I ask why, she says: “Because we worked in the kitchen and so that’s the part of us I like to focus on. And besides, relationships are complicated, as are people. The bad bits are not the whole.”

Certainly, Nigella has always been at the centre of things. At Oxford, where she read medieval and modern languages at Lady Margaret Hall, she boasts: “I was the queen of onion soup!” Another friend, the television producer Tracey Scoffield (who remembers Nigella arriving in the year below her at Godolphin & Latymer school, aged 16, “wearing enormous dungarees, her hair cut in a short bob that was shaved up the back”), recalls that she ran with a very glamorous set, including Hugh Grant and the Piers Gaveston Society, an infamous club devoted to hedonistic excess. One night, Nigella was injured as a passenger in an accident en route home from a party. “She’d hurt her back quite badly and been taken to a local hospital,” says Scoffield. Back at college, Nigella had to be carried downstairs to phone her father, the redoubtable Tory minister Nigel Lawson, then financial secretary to the Treasury. Lawson was furious that the hospital had sent her home too soon. “Well,” Scoffield remembers Nigella firing back at him, “you were the one who made the cuts in the first place!”

When I suggest to Nigella that she ran with a “fast crowd”, she laughs. “The thing is, I made friends widely. I did go out a lot, but more of the time I was in my room or the library, recharging and reading or just being exhausted – it was so intense there and I’ve always had a need to step back and dim the lights. I was a bit of an exotic outsider for the posh crowd, and I moved freely between what could be called ‘sets’, seeming to belong but slightly apart at the same time. It’s always been people who interest me, not parties or social life.”

Today, I’m talking to Nigella at home. She is chatting, as she so often does, while lying in her favourite position, upon a pile of pillows (she swears by her silk pillowcase – “good for the skin”) under the duvet in her bedroom. She’s wearing a black silk and towelling dressing gown (my birthday gift to her this year). Her loft-like room is piled with stuff: there are books everywhere, discarded shoes, Feu de Bois Diptyque candles on the go, and a mug of builder’s tea perched on the bedside table. Beside her sits a bag full of her favourite skin creams. “I really like this room,” she says, nodding up to the large skylight that overhangs the bed. “I can retreat here without that depressing sense of being huddled in the dark. It feels calm in an uplifting way, which is new to me, and I love it...” Nigella speaks very fast (she eats very fast, too), jiggling her leg as she talks, as is her habit, and rubbing her hands together when she hits on a story she’s particularly amused by. “Actually,” she continues, “there’s something rather liberating about living in rented accommodation. I’m not responsible for how the place looks and so my surroundings aren’t freighted with a sense of self. Though of course I’m so messy that, as you can see, there’s clutter everywhere. And I hate mess. I shouldn’t be buying books, since I haven’t got bookshelves, but I can’t stop myself so now the floor is like an assault course.”

As anyone who has ever seen her shows will appreciate, Nigella adores the indulgences of life – good food, good face cream, good bed linen. But she’s not spoilt. The very fact that she walked away from her marriage without asking for anything other than the contents of her kitchen is testament to that. “We were never given a lot of money as children,” she says. In 1977, she was given a first allowance of £24 a month. “My father made me do a budget!” she laughs. And despite the privilege around her she has always had a strong work ethic. She prides herself on the fact that, aged 14, she lied about her age to get a job at Ravel shoe shop. At Oxford, she waitressed at the fashionable restaurant Clements: “It always really annoyed me when friends would come and not tip, thinking it would be embarrassing. Well, of course, it was embarrassing to them!”

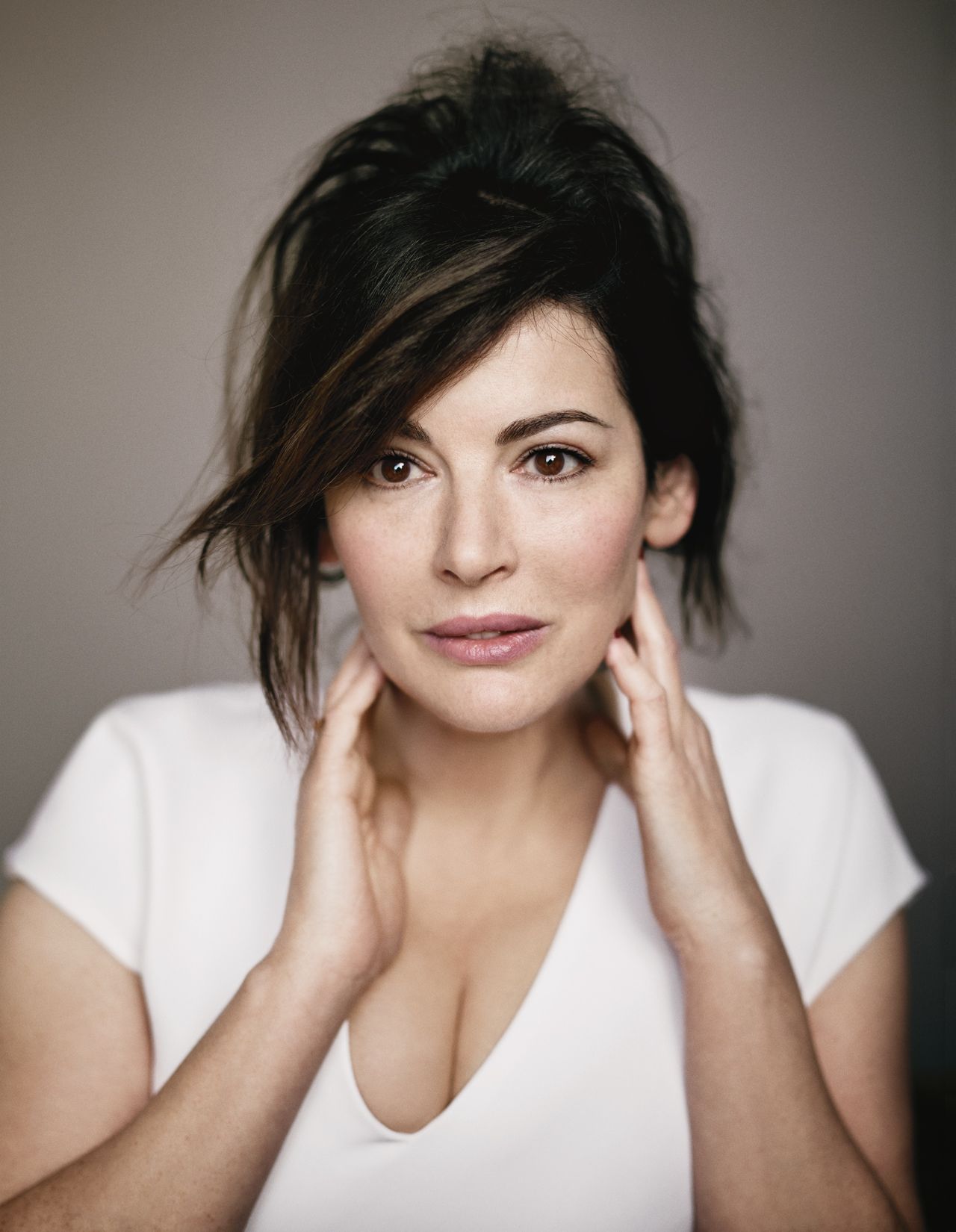

I watch her face as she talks away. It really is mesmerising. It always has been. Magazines lined up to photograph her as a beautiful undergraduate, and people have always been captivated both by her intimate nature and the similarly intense vulnerability that flickers behind her eyes; despite her incredible self-possession, one is always somehow aware of her innate inherited anxiety.

Now 54, her skin, which has barely ever been exposed to the sun, is luminous and smooth, like that of a small child. Her eyes are Nutella-brown. Hers is a strong face, with dark brows and wide cheekbones and a soft mouth. She looks perfect, even without a scrap of make-up, and is shot for Vogue wearing only mascara, a smudge of blusher and a dab of lipgloss. On television, she is famous for a signature look of heavy kohl, false eyelashes and luscious, mahogany-coloured hair, but she seems much younger and more vulnerable without it. “Make-up is not a mask, it’s armour,” she says of her appearance. She doesn’t enjoy discussing her looks, much less scrutinising them: on the Vogue set she wouldn’t even look at the screen. “I was terrified of being photographed without make-up,” she says. “And I hate having my looks talked up. It always makes me feel I’m going to be a disappointment in the flesh.”

Although my friendship with Nigella drifted in our twenties – during which time she established her career in journalism – we reconnected in the mid-Nineties when she started writing a food column, for Vogue, from the point of view of a working mother. We met at a dinner party at an editor’s house: she was removing the beards from a sinkful of mussels and keen to introduce me to her new husband, John, a brilliant, darkly funny writer with whom she lived in Shepherd’s Bush. Life bumped along until, one day late in the summer of 1997, I ran into John. “How are you?” I asked. “I have cancer,” he replied, as though I had asked him about the weather.

At first, I was scared to call Nigella. She had not long before lost her mother and her sister Thomasina to cancer, and this seemed the cruellest blow. In fact, she was in coping mode, managing two small children and John’s sickness with practical efficiency and a total disregard for self-pity. “It’s strange. I had always thought of myself as weak, but I had to be strong,” she says of that time. “And I don’t admire that strength because it simply hides the weakness from others. Besides, it wasn’t a choice, it just had to be.”

I could say that those were dreadful dark days, but they weren’t. Even though John became sicker and sicker (and it became increasingly hard for others to understand what he was saying because his tongue was cut out), life carried on. John was instrumental in persuading Nigella to write a cookbook; she only undertook How to Eat because it meant she could be at home with him and make money at the same time. The irony that John couldn’t eat a morsel of her food was not lost on either of them. Their house smelt of cake in the kitchen and medicine upstairs. “I wrote that book in six weeks,” she says. “I once wrote 28,000 words in a day. I wrote fast because it had piled up in my head and I just let it out. I was so late with it that I didn’t have time to worry any more, just write. And that’s pretty well how I do all my books.”

How to Eat was a huge success, and the subsequent TV spin-off (starring her family and friends as dining guests) made Nigella a household name. She and John became public figures: his weekly columns inspired both compassion and adoration for the couple, and her doe-eyed charm seduced millions of viewers. Yet, despite this, and her instinctive shyness, Nigella never found her extraordinary public profile unusual. “I know this sounds odd, but I just don’t experience myself as a ‘public’ person,” she explains. “I just feel like me. Maybe if I lived a premiere-and-red-carpet kind of life, I’d feel differently. There’s an old saying that what other people think of you is their business. But, apart from anything else, I don’t have the ability to be anything other than myself.”

They were strange, fun, sad days in which nothing was normal and yet nothing was abnormal. There were constant dinners, friends around the kitchen table – some dinners were filmed, some weren’t. Nigella has always liked having people around her – I think their presence stops her from, as she puts it, “going under”. A manicurist would come every week before the filming (it was important her hands looked good in the shots) and we would get our nails done, chatting and gossiping. John would be well at times and less so at others: he was anarchic, acerbic and angry. He could only eat by feeding himself through a tube. His party trick was to fill the syringe from a champagne or vodka bottle and inject it intravenously.

Publicly, they were a steadfast, devoted couple. But privately, Nigella’s life was beginning to move in a new direction. In April 2000, the literary agent Ed Victor hosted a dinner at the Ivy for the editor Tina Brown: among the guests were the writer James Fox, Geordie Greig, Barbara Amiel, Nigella, and Charles Saatchi. Ed recalls how he had called Saatchi the day before to make sure he was coming, as he could be “elusive”. “I’ve put you next to Nigella Lawson,” Victor remembers offering by way of encouragement. “No! Please don’t sit me next to her,” Charles begged. “She’ll intimidate me.” Ed ignored his request. Halfway through dinner, Nigella excused herself, and Saatchi turned to Victor: “I have fallen in love!”

Quite by chance, I, too, was having dinner at the Ivy that night, and remember Nigella stopping by our table. “I’m sitting next to Charles Saatchi,” she told me. “He’s very entertaining.” Charles became friends with both Nigella and John. He invited John to his regular Scrabble game at Montpeliano’s restaurant in Knightsbridge. The men got on well together – they were both Jewish, funny and fiercely bright – and if Charles was in love with Nigella (and why wouldn’t he be? Half of England was), he kept it to himself. Saatchi made a glamorous addition to their crowd. He went out of his way to be charming to everyone. He was rich and famous and full of life, and there was something faintly unpredictable about him which made him compelling.

John died in March 2001. In the intervening weeks, Nigella spent a lot of time with Charles. He was good at making things OK: I think she was so exhausted by life and death that she was only too happy for him to take charge. Six months later she called me over to her messy office and told me she had fallen in love with Charles. I was happy for her. John had been so sick for so long, I thought she deserved the happiness. And she was happy. It was lovely to witness. With her young children, Bruno and Cosima, she slowly made the transition from their home in Shepherd’s Bush to a new life in a huge house on Eaton Square.

Unlike the house in Shepherd’s Bush, which had been homely and chaotic, Eaton Square was vast and filled with Saatchi’s art: a Duane Hanson sculpture of a woman and her shopping sat in the entrance hall, so lifelike that guests often made the mistake of saying hello to it. A Marc Quinn blood head sat frozen outside the kitchen. Tracey Emin’s My Bed had its own room. It was impossibly grand, luxurious and somewhat overwhelming, not unlike a theatre set with trees in the entrance hall and enormous flower arrangements everywhere (all fake). Nigella’s kitchen looked out on to a stairwell and had nothing like the welcoming atmosphere of her old home. Rather than attempt to film the TV programmes there, Nigella recreated the cosy domesticity of her previous kitchen in a studio in Battersea.

Nigella was by now very famous – a national treasure, according to some. She was also wealthy. But she had earned the money and delighted in sharing her success, often buying me lavish gifts. “George Gissing once said that what he hated about being poor was not being able to be generous,” she explains. “And I know this sounds naff but if I can’t share any good fortune I have, I can’t enjoy it for myself. Actually, I’m not sure how comfortable I am spending money on myself. I do it when I can, but I almost feel more ‘me’ when I can’t.”

Charles, too, was fond of the grand gesture: he once bought her scores and scores of copper cooking pots because she had said they were her favourite. And he loved to squire her on shopping trips to Selfridges after a lunch at Scott’s.

Together they were supremely generous, and, in the early days, entertained regularly at their new home. Nigella made chicken soup for Woody Allen, and supper for Mike Nichols and Stephen Fry. The crowd was intellectual, artistic and fun. People would joke that had there been a remote control at the table one could change channels from Simon Schama to Harry Enfield. Or Salman Rushdie to David Walliams. At the table, Charles liked Nigella to sit close to him, whispering in her ear while chain-smoking Silk Cut Ultra Lights. They clearly adored each other. But the atmosphere at the table always depended on his mood. And his mood was variable.

Nigella got on with doing what she did best, transporting her beloved office team to the house and working on a new book. She wrote at home and shot the pages in her dining room, which became a sort of immense prop room filled with Nigella’s “finds” from eBay. (She has a weakness for online shopping for kitchen paraphernalia: “I can spend hours looking for vintage champagne saucers – I recently found 12 for £11 – or a book I want on Abebooks.”) Visiting her, everything seemed familiar, yet not. Hers was no longer the house you “dropped in to”, and Charles was not one to sit around the kitchen table cracking jokes and sharing stories.

Yet Nigella kept busy. Nigella is always busy. She has written nine books since 1998 and produced scores of episodes for her TV shows – both here and in America. I have never known her not to be immersed in a project. “It’s really important that I keep working,” she says. “It’s how I hold on to myself.”

When the family left Eaton Square for a spacious house in Chelsea, she got the kitchen of her dreams and loved working in it. She also filled the house with real flowers. (People say that when she left Saatchi, the fake flower arrangements were swiftly reinstalled.) The entertaining – which had ground to a halt at Eaton Square – was revived for a brief period and then dropped off again, replaced by dinners at Scott’s or 34 or occasionally Locanda Locatelli.

I think work was also a welcome distraction from her creeping sense of dissatisfaction. Things had become less blissful. Nigella is the first to say that she has a genetic tendency towards depression, but this seemed different. Her anxiety was evident. She was also very isolated. Charles liked to watch TV, and he liked her next to him as he lay on the bed, watching his favourite shows from late afternoon to midnight. Although there was no denying theirs was an enduringly passionate relationship, she did once say wistfully to me that she felt she had spent her forties in front of a television screen.

No one can know what really goes on inside a marriage. When, six months ago, a friend called to ask if I had seen the now famous pictures taken outside Scott’s, I was horrified. I sent her a text. “Are you OK?” She replied, “I will be.”

Charles is a volatile and complicated man, Nigella an anxious-to-please and complicated woman. The marriage was over. Just under eight weeks later they were divorced. But she won’t be drawn on it. When I ask her to comment on what happened for Vogue, she replies, “I never wanted to speak in public about my divorce. I had to in court and I hated doing that. I won’t do it again.” She doesn’t read what is said about her in the papers – she has given them up in order “to preserve my innocence, if I can put it that way” – and is equally keen to protect Cosima and Bruno, now 20 and 17, from unnecessary exposure. Of the intense media speculation that has surrounded the family, Nigella will only say: “Being young is difficult.”

Both children are extremely close to their mother; you get the impression they are a team. Bruno is like his father: charming, funny and intuitive. Mimi is clever, private and elegant, with an edge. They are clearly blossoming in their new life.

In the wake of the court case, Nigella has kept her head down. The Taste – which was filmed in Los Angeles and then London – has been a welcome distraction. And, in lieu of newspapers, she has buried herself in her books. “I’m greedily reading and re-reading Philip Roth,” she says, as she lists her recent passions. “And David Copperfield is my favourite book because it exemplifies what it means to be a person.” She’s revisiting Dante and Petrarch (in Italian, with the help of her trusty English/Italian dictionary, held together with Sellotape and stained with Marmite). She has also finished a new translation of Proust, and a lot of what she calls “new age nonsense”. “I’m ready to start thinking,” she says. “I love what I do, but there are other parts of my brain that I haven’t flexed in a professional way. I do sometimes think that I’ve let the more analytical part of my brain slump slightly. I mean, I do like writing about food but there is so much that interests me...”

Perhaps the past year, and the realisation that she is now a single mother, have galvanised her ambitions once more. “I don’t think like a businesswoman,” she says. “But I do still have to think about putting a roof over our heads and supporting my family. To that end, I’m just finishing up on a unified re-issue of all my old titles which has been in the pipeline for the past year, and at the same time trying to let a new book come into being. Oh, and I’ve been working – in a cottage-industry way – on an app which, if it works, could be deeply thrilling. Sometimes it does feel as if I’m a computer with too many tabs open...”

Nevertheless, Nigella still has a terrific sense of fun – and naughtiness. After New Year’s Eve, when London was cold and grey, I called her and suggested we escape to Claridge’s for the weekend. We had a laugh. We ordered room service (club sandwiches, burgers with blue cheese, and lots and lots of fries) and watched movies in bed. We devoured packets of Mr Trotter’s Pork Crackling out of the mini-bar, and then ordered more. We never once bothered to change out of our pyjamas, nor left the room. Perhaps surprisingly, Nigella was on the best form I’ve seen her for a long time. There is no rancour or bitterness in her manner.

“I’ve been able to take pleasure from things again,” she reflects, as she puts the kettle on for yet another cup of tea. “For example, I had an impromptu dinner party recently here the other night and suddenly, as I was cooking the stroganoff, I felt an incredible sense of comfort come over me because I realised there was nobody coming who I would be uncomfortable in front of just wearing socks and leggings, and no make-up. I think that’s important, because as you get to a certain age in life, although it’s lovely to meet new people, I feel if I am happy to see them in my PJs and dressing gown then they are the people I really need in my life.”

Days later, I attend a belated “office party” Nigella is throwing for her team. The guests are an idiosyncratic bunch – they include her fishmongers (who helped move her kitchen belongings out of the marital home), her agent, make-up artist, divorce and libel lawyers, Pilates teacher, assistants and greengrocer; a perfect example of Nigella’s long-held talent for mixing ingredients. It is a great party. And, as we spill out into the street late that evening, it strikes me that for the first time since I’ve known her, she is now able to make decisions based on what she alone wants to do. And how relaxed and happy and empowered that makes her seem. But, of course, that’s only an opinion...